Interview with Faculty Fellow Peter Kastor

With the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, the nascent “United States of America” faced a daunting new challenge: creating and staffing a governmental mechanism, transforming the collective vision of the American Revolution into interconnected cogs and components. “Tasks ranging from the heady — creating a federal court system and federal jurisprudence — to the seemingly mundane — delivering the mail — all provided ways for the federal government to reinforce the notion that the states were indeed united,” says Peter Kastor, the Samuel K. Eddy Professor of History and American Culture Studies, and a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. How did this experiment in federal government come to be? Kastor tackles this question in his current book and digital project, “Creating a Federal Government.” Here, he tells us about his quest to document this origin story, which has already yielded some surprising stories about the founding of the United States.

Briefly, what is your book/project about?

“Creating a Federal Government” is a multiplatform project that combines a book and website to reconstruct and understand the federal government during its first decades from 1789–1829.

My goal was to tackle a specific question: How did Americans govern themselves during the Constitution’s first tumultuous decades?

Sounds like a simple question, doesn’t it? After all, the Constitution is a commonplace subject in schoolrooms and public debate. Historians have long concerned themselves with politics of this era. And bookstores and websites alike are filled with biographies of the Founding Fathers.

Yet for all those books and all those classes, some basic questions remain unanswered: What did the federal government do and how did it do it? Who served in the federal government and where? How large was the federal government and how did it change over time?

Why a book and a website?

The book and the website are both motivated by my goal of crafting a project that will challenge scholars and engage a general audience.

I always imagined the book as a narrative story, one that would explain how the Founding Fathers sought to create and run the complex institutions of government. But I also wanted to tell the story of what it was like to serve in that government, and that topic could only be addressed through a quantitative analysis of the federal workforce. As I built my dataset, I became increasingly excited by the prospect of sharing that data through a publicly accessible website.

The book and the website complement each other. The website’s data informs the book; the book has guided my planning for the website. The website invites users to ask their own questions; the book constitutes my own interpretation of early federal governance.

Can you give us an idea of the website’s scope? How might others consult it?

The data for the website currently consists of the following:

- 9,467 appointees to civil office (not counting the Post Office) with 24,926 records of federal employment

- 5,186 records of nominations to civil office submitted to the Senate for advice and consent

- 7,702 officers in the United States Army

- 3,504 officers in the United States Navy and Marine Corps

- 32,132 postmasters in 8,360 local post offices

- 28,000 letters from people requesting federal appointments or recommending others for federal appointment

The website will enable people to find or track the career of an individual federal employee or ask broader questions about government institutions. The website will also map the locations of federal governance, identifying where federal officials served and also how individual federal officials moved from one place to another.

Can you preview any stories you uncovered?

I remain fascinated by the people who show up in these federal employment rolls.

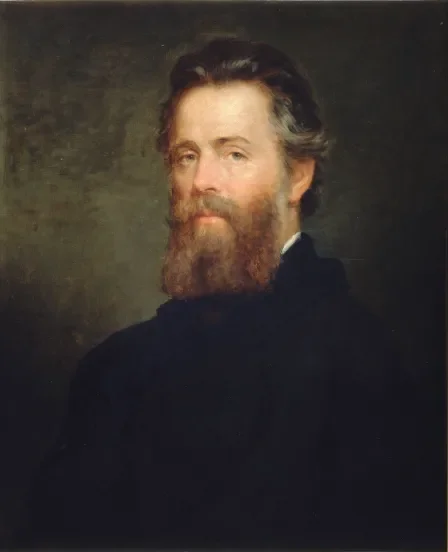

It seems that federal employment was an important waypoint for writers. Washington Irving served as a diplomatic secretary in London. James Fenimore Cooper was a midshipman in the navy. Herman Melville was a customs inspector in the 1860s, and his grandfather shows up in the database as a customs official in Boston.

Meanwhile, the membership of federal workforce was not so monolithic as it might appear. But people of mixed race ancestry show up in a variety of roles, including the crucial task of translators between the United States and native peoples. Meanwhile, women worked as lighthouse keepers, postmasters and marine hospital nurses.

This hardly means to the federal government was an engine of inclusion. To the contrary, the vast majority of federal employees where white men, and one of the principal tasks of the federal government was to secure white supremacy. But that’s what make it so interesting. How did people seek to navigate those boundaries of race and gender?

How has this massive project evolved over the years?

The changes are easy to explain. New technologies have improved the ability to interpret and visualize the data. But I’m more struck by the continuities. The fundamental challenge of converting the idiosyncratic records of the early American republic into an organized dataset that a computer can understand is as difficult now as it was when I started.

Why is this the right time for this project?

At this very moment, Americans are debating the proper role of government on one hand and the meaning of the Founding Fathers on the other. To answer these questions they have often looked to the ideas that structured the federal government, in the process ignoring what the federal government did. My project asks people to consider the government Founders actually built, in all its possibilities, limitations and prejudices.

What emerges is a federal government that was larger and more ambitious than many contemporary conservatives might acknowledge, but more clearly restricted than many progressives would wish. We also see a government that sought to promote equality and opportunity for white citizens while also establishing and securing racial supremacy.

Headline image by Ralf Steinberger CC-BY 2.0