Anika Walke is the Georgie W. Lewis Career Development Professor and associate professor of history in the Department of History, with affiliations in the Program in Global Studies and the Departments of Jewish, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies; and of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Demilitarization and denazification — when Vladimir Putin announced the goals of the Russian attack on Ukraine, I perked up. As a scholar of World War II and Holocaust, these words are part and parcel of my classes on the aftermath and the legacies of war and genocide. But what I teach my students as the takeaway from the Allied forces’ plans for postwar Germany is a triptych. There are three Ds: denazification, demilitarization and democratization. While Putin alludes to campaigns that the Allies agreed upon, twisting history and the anti-Nazi consensus into unrecognizability, a central element of the postwar effort remains unnamed, for good reason. There is no question that the war has been started by an authoritarian regime with protofascist tendencies, and the stated goals are pure distortion of the war of destruction we see unfolding in the cities and villages of Ukraine; it has nothing to do with denazification and demilitarization.

Apart from this twisted presentation, I am left pondering three aspects of the war that not only keep me up at night, but which profoundly reshape the world we inhabit and which will greatly reshape our scholarship as well. The discussion about German armament support for Ukraine, the violence against people and land that evoke memories of scorched-earth policies during World War II in the same territory, and the situation of already more than 1.5 million refugees mark this war as a turning point. My view and perception of the current war is shaped by categories and judgments deeply rooted in the commitment to fight the revival of German nazism and militarism, to take responsibility for the memory of German atrocities against European Jewry and the people in the occupied territories, and a feminist and anti-racist sensibility I developed first and foremost as an activist against European, especially German policies against refugees and migrants. What follows are at times disconnected thoughts, yet in the spirit of this blog’s aim to capture the moment, I hope for the reader’s openness to an unfinished articulation of new and older concerns.

I was born and raised in East Germany, experienced the breakup of the GDR as a teenager, and came of age and grew into a political subject and activist in the late 1990s, i.e., at a time that thousands of refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chechnya, Nigeria, Cameroon, Iraq, Cote d’Ivoire and elsewhere fled war and destruction and struggled to enter what we then began to call Fortress Europe. My scholarly, now professional profile developed in conversation with and as a result of these experiences — to analyze just why especially Germany pushed an increasingly impenetrable border regime that made it nearly impossible for refugees in search of asylum to reach European territory, one can hardly avoid a deeper look at how the two German societies dealt with (or better: did not deal with) the remnants and legacies of Nazi ideology. Racism and antisemitism never went away, and the xenophobia, violence and restrictive laws governing residence, work and living arrangements that refugees have encountered since the so-called Asylum Compromise of 1993 cannot be understood outside of this framework.

Simultaneously, alongside many others I realized that despite years of schooling in the anti-fascist spirit, we had learned rather little about World War II, about German atrocities against Jews and civilians in Eastern Europe, Greece and elsewhere, or about the exploitation of forced laborers in German companies, farms, municipal services and private households. My West German peers knew perhaps a little more, but the extent of antisemitism and racism that drove much of the wartime violence was not taught or addressed widely in their schools either. Increasing calls for reparation and compensation for labor in ghettos, for forced labor, for the theft of Jewish property once the Iron Curtain was gone were accompanied by the recognition that there is a lack of knowledge and understanding of the history and legacies of the German occupation regime in Eastern Europe. This recognition drove many of us into archives and into the homes of survivors who were eager to speak. It was also a recognition that made the limitations to German military capacity after World War II — beginning with the complete demilitarization in 1945, continued with strict limitations to the legitimate deployment of Bundeswehr troops — appear not only justified but necessary. The Nationale Volksarmee, the East German army, was also focused on defense operations, yet consistently on alert due to a perceived threat from NATO. In any case, the first out-of-area operation of the “reunified army,” first in Iraq, then in Kosovo, marked a caesura that caused much debate and protest. For the first time since 1945, German soldiers were actively engaged in warfare. In light of this, I am struck by the celebratory attitude I observe, in Germany and internationally, that accompanies German chancellor Olaf Scholz’s announcement to send weapons to Ukraine and create a special fund of €100 billion for the Bundeswehr. It is not only striking that, again, it is a government formed by Social Democrats and Green Party, supported this time by the Liberals, which proposes and affirms this drastic change in German military and security politics. It is also worrisome that the announcement was greeted with standing ovations in the German parliament, not with a somber, calm and thoughtful response one may have expected, given the weight of this declaration. The applause was an eerie reminder of the reactions to Martin Walser’s speech in Frankfurt’s Paulskirche in 1998. In accepting a major book prize, Walser called for Germany to be recognized as a “normal” society and a liberation from the “moral club” (Moralkeule) and “threatening routine” (Drohroutine) that the memory of the Holocaust poses for Germans. If Walser’s speech was the moment when the Berlin Republic breathed a sigh of relief from oppressive Holocaust memory, which would then develop into the touristification of this memory, culminating in a “memorial that one likes to visit” (Gerhard Schroeder on the Berlin Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe), what does the applause for pouring billions of euros into the German military and the active intervention in a war fought on territories that were razed to rubble by German troops a few decades ago mean? In recent days, more and more members of the Social Democratic Party speak out against Scholz’s commitment, citing the roots of the party but also the disastrous approval of war credits by that same party in 1914. While there is clearly a need to support the population of Ukraine against the war of aggression, started by Russia, we ought to be wary of remilitarization and rearmament everywhere.

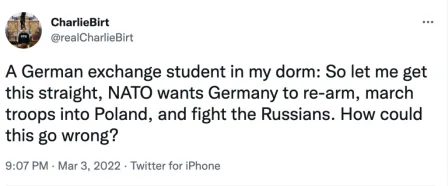

A few days ago a note began to circulate on German Twitter, stating: “As a German I just want to get some things straight. The entire western world wants us to: Build up a huge army, March through Poland, Fight the Russians if needed. Just writing it down so there is no misunderstanding in the future.”

This is no laughing matter. The war of annihilation that German troops waged against the Soviet Union beginning in 1941 is the reason why German military capacity was curbed in 1945 and, originally, German soldiers were not ever to be sent abroad again. The tweet evokes the destruction brought upon Belarus and Ukraine during World War II, when German troops killed up to 90% of the Jewish population in the area, set fire to and razed to the ground thousands of villages together with their inhabitants, and destroyed fields, forests, houses and factories in such a way that it took decades to rebuild. Most survivors of the Holocaust and of the terror in the villages that I have interviewed in the last 20 years conclude the conversation with some version of “may there never be war again.” Watching footage and photographs from Mariupol, Irpin or Demidov that show the devastation left behind after Russian bomb raids and shelling, I think of this generation, traumatized then and traumatized anew now. As former citizens of the USSR, they had been a powerful voice in the postwar period. They were often wrongly collectivized into a Soviet whole that neglected the different kinds of persecution and violence they had experienced during the war, yet they stood unified in their plea against another war. In recent years, I noticed a shift in interviews I conducted in Belarus. Beginning in 2016, shortly after Russia had annexed Crimea, “the Ukrainians” emerged as major perpetrators of violence against Belarusians, as civilians that suffered less from German violence, in other words, as enemies rather than fellow victims, which the majority of the Ukrainian civilian population had been. The propaganda machine in the aftermath of the annexation worked, even in the Belarusian-Latvian borderlands. Now we see Holocaust survivors in Kyiv pleading for an end to the shelling, recorded on a smartphone camera in the bunker, while a 91-year-old survivor of the Leningrad Siege is trapped in her home in Kharkiv, threatened by Russian air raids and shelling.

The memory of World War II, or the Great Patriotic War as it was (and partially still is) called in the Soviet Union and its successor states, has never been so acute and so fragile and politicized as in the years since 2014. The so-called Banderovtsy, members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists under the leadership of Stepan Bandera, were both venerated by some and cause for the condemnation of Ukrainian nationalism for others. Both the non-president Aliaksandr Lukashenka and activists against election fraud and authoritarian repression in Belarus mobilized the memory of World War II to insult each other and mobilize the population. Lukashenka presented the opposition within the country as agents of the West that is staging another attack on Belarus akin to the German invasion of 1941 on the one hand; protesters described the terror and brutality of special police forces against protesters as the work of Gestapo or karateli, a term usually reserved for the henchmen of the German occupation regime on the other. Lukashenka and his ruling elite radicalized the rhetoric in 2021, when supporters of the opposition were equated with the collaborators of World War II who waged war against their own compatriots. The 2021 law “Against the Rehabilitation of National-Socialism” provides the foundation for the prosecution of pretty much anyone protesting the current order, as it operates with a loose definition of extremism that for instance determines the use of the white-red-white flag (colors popular among the protesters but which have also been used by the Belarusian National movement and some of the collaborationist formations of World War II) as a sign of extremism and veneration of Nazi ideology. The crowning moment of this campaign is the revised portrayal of World War II violence as a genocide of the Belarusian population. According to the new law “On the Genocide of the Belarusian People” of January 6, 2022, the denial of the genocide of Belarusians is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. The crux of the law is in its motivation to denounce protesters against the government as supporters of the genocide of Belarusians: Again, the use of the colors white and red signals support for nazism, i.e. the genocide of Belarusians. The law relies on a distorted definition of genocide and skirts the Holocaust. Yet, resorting to genocide as the crime that, everybody agrees, must be condemned, the law has real power, as it justifies the harshest interventions against those supposedly culpable of the crime. How many of the over 1,000 political prisoners currently held in Belarusian prisons will be charged with these crimes is unclear, but I fear there are many — the first trial against Ales Pushkin, a painter, is currently under way. Lastly, any scholar questioning the genocidal intent or proposing a different, more nuanced view of German occupation policy is liable to prosecution.

Putin justified the invasion of Ukraine on February 24 with the need to prevent a genocide as well, this time, of Russians in Ukraine. The charge has been debunked, on this blog and in a powerful statement of a large international group of scholars. What I note here is the worrying trend of weaponizing history and the charge of genocide and placing history in the service of current political agendas. This trend is not new, yet it has not been used as a basis for a full-on military assault that, according to Volodymyr Zelenskyy, in turn constitutes genocide. What happens, when words get tossed around like this and result in large-scale destruction? What will it do to our ability to study the past? There are already signs that Belarusian attempts to establish the crime of genocide foreclose more open-ended studies. Apart from the risk one takes in proposing different analyses, more technical obstacles are on the horizon: Archival material is sequestered and inaccessible for scholars as the Office of the Prosecutor General is working with it to establish the charge of genocide. Interviews by prosecutors with Holocaust survivors retraumatize elderly men and women who feel pressured to give accounts in line with the political task. Scholars worry that insensitive interview-interrogations will discourage survivors from participating in further interviews even by well-trained oral historians. The destruction of museums and archives in Ukraine and the arrest of cultural activists and scholars in recent days create massive obstacles to the study of the past. Not even to speak of the many scholars from Belarus, Ukraine and Russia who have lost their lives or have fled or are trying to do so and whose expertise will be missing. I dare wonder whether the scorched-earth policy we are witnessing also signals an attempt to destroy archival materials such as those of the KGB that had been made accessible in the Ukraine, a step that remains unimaginable in Russia or Belarus. In sum, the Russian assault, which would not have been possible without the authoritarian repression in Belarus, marks a turning point in the politics of history as well as regarding how and whether we can study the past, a past of violence against people and land in the same territory that provides the screen for our view of the current destruction and violence.

Wars have accompanied the breakup of the Soviet Union, of Yugoslavia and of the socialist bloc more generally, and all of them triggered mass flight. During my first long stay in Russia, I volunteered with an organization supporting refugees from Chechnya. Their stories resembled what I had encountered in the late 1990s in Germany, when thousands came from Bosnia-Herzegovina: violence and traumatization at home, and lack of support, rejection and abuse in the place of refuge. As of today, more than 1.6 million people have left Ukraine and sought refuge in neighboring and other European countries. Many more will follow. The number of people displaced internally, within Ukraine, is estimated to be much higher. Those who manage to leave the country receive a usually warm welcome. Just months ago, the Polish government adamantly refused to admit refugees that had been pushed over the Belarusian-Polish border in a disgusting scheme of the Belarusian government, designed to expose the European double-speak of human rights protection. Now, more than 1.4 million Ukrainians are in Poland. More than 80,000 arrived in Germany, and other countries have admitted large numbers as well. While much of the concrete supply of housing, food and care is provided by volunteers, the governmental position toward them is starkly different from anything we have seen in recent years, even during the recent arrival of refugees from Syria. Enabled by a Temporary Protection Directive of the European Union, Ukrainian refugees receive the right to live and work in the EU for up to three years. I commend the quick and helpful response, of both people who offer their couches and spare bedrooms, share their food and help in any other possible way, and of authorities that work hard to bring the refugees to safety. And yet, it gives me pause. Why is this possible now, and not other times?

Clues are offered by a closer look at what is happening now: students from African and Asian countries who were trapped in Ukraine when the first bombs fell and were sent back at the border or not allowed to cross. Roma are subjected to additional scrutiny at border checkpoints and when European organizations hand out food and other supplies. Queer Belarusians and Ukrainians struggle to leave Ukraine and report insult and abuse. The unequal treatment is glaring and confirms the old truism that some refugees are more welcome than others. Black and brown people, people who are somehow less European because they are Muslim, or young men traveling without families have been greeted with hostility and violence, always expected to “go back.” Note the long and arduous debate about admitting refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo back in the 1990s. Eventually, refugees were allowed to come, but for a limited time, and every participating European country offered a particular quota, capping the number of how many refugees would be allowed in. I remember the Bosnian women, traumatized by war and rape and in need of long-term care and therapy, always fearing the time they would have to go back and missing their relatives who had been sent to a different country. The Chechnyan woman, hiding that she had been raped by Russian soldiers from her husband and children while also fighting with the immigration authorities for the right to stay in safety. Perhaps European politics is better now and societies have learned.

And yet. Refugees from Yemen and Afghanistan are moved from their accommodations and placed in remote housing, away from schools, friends, language classes and other networks they have been building in order to make room for Ukrainians, the majority of them women and children.

[Translation: In Fuerstenfeldbruck, about 100 refugees from Ukraine are to be accommodated in the so-called Anchor Center. Current residents, refugees from Afghanistan and Yemen, were simply transferred to Waldkraiburg, a town more than 100 kilometers away and thus cut off from their support structures.]

There are similar reports from Berlin and other cities. Asylum seekers in Germany are typically held in so-called Arrival Centres for months on end. If they are lucky, they are transferred to other housing later on, but these homes are often located in remote areas with limited access to urban life, schooling, etc. Strict laws regulate their ability to travel within the country or to work, condemning many to idleness and poverty. Life in collective settings with little privacy and exposed to abuse by staff and law enforcement exacerbates the risk of mental health crises and physical injury. Detention centres in Poland, Greece and other countries of the EU borders are places of danger and violence. The Mediterranean Sea has become a mass grave for thousands of refugees who have tried to reach European shores since the late 1990s. Institutional and everyday racism send a clear message: “We do not want you here.”

The refugees from Ukraine are at no fault. What I flag here is the differential treatment of refugees from war and persecution. While some are questioned and cause for hostility in the one case, the refugees of the last two weeks have not only literally overrun the EU border, they are also let in with a smile. When someone put it bluntly and asked for their support because they are “like us,” he hit a nerve. They are not only white. They are also fleeing a known enemy — Russia. Russia is the aggressor, no question. And yet. I refuse to accept that we spiral into a new bipolar world, with Russia opposed to everyone else. I also refuse the hierarchy of nations and races that is being reestablished in the wake of this confrontation. Everyone fleeing war and persecution requires support, as quickly and as generously as possible. The current reaction in Poland, Germany, France and elsewhere shows that a lot is possible.

These snapshots are what they are — snapshots. The return of war and militarization, the revisionism of history and return of trauma, and the problematic treatment of refugees and continued racism within the European Union toward indicate what is to come. The Russian attack lays large parts of Ukraine to rubble and ash. It also lays bare fault lines within Europe and European countries as a whole that we ought to pay attention to. Memory laws were first introduced in Western European countries, but they seem to have become the tool of choice of dictators to crush internal dissent and to re-nationalize a view of the past that a project such as the European Union had tried to overcome. Is there a protection against the further abuse of history? I do not have the space to discuss the tendencies within the European project that undermined itself by promoting thinking in national and racial categories. Policies on refugee admission are telling. Alongside a focus on developing equitable and generous policies that support refugees irrespective of their origin and identity, overcoming a deep-seated racism that undergirds the formation of European societies is of the essence. A first step would be to extend support and solidarity to everyone fleeing, not only from Ukraine but also from Belarus and Russia — those who want to leave are surely not in support of their so-called governments. If we begin to follow the divisions created by Putin and Lukashenka, we follow their lead of distorting our shared history and present as determined solely by national categories.

Headline image: Day 11 of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Przemyśl Railway station [Poland]. Refugees arriving from Ukraine. Photo by Pakkin Leung, CC BY 4.0.

This article is republished from New Fascism Syllabus under a Creative Commons license (CC BY NC-ND 4.0). Read the original article.