Varun Chandrasekhar is a Graduate Student Fellow and a PhD candidate in music theory in the Department of Music. His dissertation, “Being and Jazz,” seeks to explicate the life and music of Charles Mingus through the lens of post-war French existentialism.

Listen to anyone who knows anything about the genre, and they will tell you jazz is all about freedom. But what does freedom actually mean? To some, freedom is defined as the ability to self-govern; to others, it is the right to participate in a democratic society; and to capitalists, it is our ability to participate in the economy. In discussions of jazz, these definitions of freedom are often imported wholesale, often without unpacking the complex contradictions that emerge from these competing definitions. Within such a paradigm, two schools of thought emerge: First, jazz is the sonic encapsulation of American democracy, an idealized world where everyone melds together; or, second, jazz is the cacophonous Black rebellion to achieve the equality required for such a democracy to properly function. Ironically, these two positions both rest on the conception that freedom is an unquestioned good.

My dissertation challenges the rather simplistic approach to freedom. Around the same time jazz gained its status as an “art” music, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was on the other side of the globe presenting a radically different conception of freedom. In Sartre’s view, since we can think, we are free, and thus always free to mold ourselves in whatever shape we want. But Sartre does not just think we are free to define ourselves however we please. Due to the structures of the world (e.g., the laws of physics, the state of technology, laws, etc.), our freedom is limited. While Sartre dedicates volumes to unpacking these restrictions on freedom, his main focus is on how other people limit our freedom. Since other people are free like I am, they gaze upon me in the same way I gaze upon them. In this sense, I develop my sense of self only by considering how I appear to the Other. I am defined by the Other, and thus, the Other, through their ability to define me, restricts my freedom. Thrown in the world without recourse, we are left with no choice but to take on the burden of our restricted freedom, constantly recomposing ourselves to rise to the situation we find ourselves in. To Sartre, freedom is not liberation so much as it is a responsibility to uphold one’s morals, whatever they may be, in spite of the realities the world places upon us. Freedom is just the anxiety of finding out who you really are.

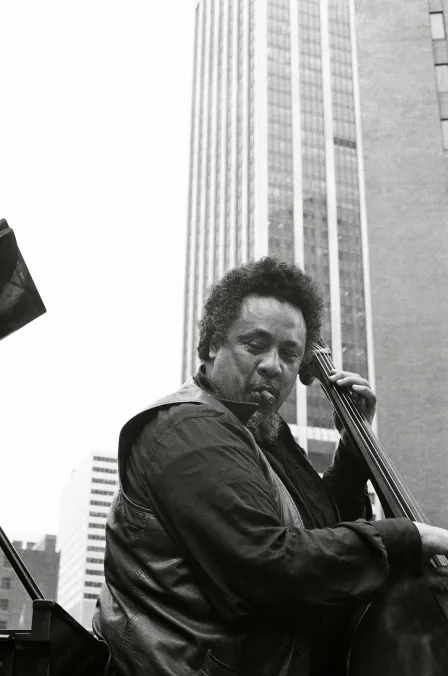

I argue that Sartre’s desire to complicate freedom presents a much more compelling description of jazz musicians. Consider Charles Mingus (1922–79). Although Mingus is best known as a jazz bassist and composer, he titles the opening track of his solo piano album Myself When I Am Real. How surprising that the rarely bashful (and, in fact, often abrasive) bassist would frame this intimate work as the “real” Charles Mingus. But upon inspection, it seems difficult to understand what man is actually behind the curtain.

A tour-de-force piece, the seven-minute, semi-composed, semi-improvised number runs through several themes that move through moments of destructive storm-like turbulence, serene chorale-like textures, jerky and funky off-beat rhythms, and respites of brevity and light-hearted play. Aware listeners will hear influence from various sources ranging from Charlie Parker to Duke Ellington to Igor Stravinsky to Fredric Chopin and everyone in between. The piece often returns to similar gestural ideas but does not conform to a prescribed form. In some formal archetypes, such as Sonata Form, themes can be thought of as characters, and over the course of the piece, the interaction of different themes comes to represent an abstract sense of a plot. That doesn’t happen in Myself When I Am Real — the ideas emerge freely. Unconstrained by a preordained shape, there is no stable subjectivity to latch on to (a hallmark of many of Mingus’ compositions).

Through his musical unpredictability, Mingus begs a more introspective question: Who is the real Charles Mingus? Is he the bowling ball of a man who would berate audiences if he didn’t feel like they were paying close attention to his music, the sensitive romantic painstakingly retrieving every melody from the depths of his psyche or the goofball who was always quick to a joke? The reality is that Mingus was all of them, all at once. Friends and lovers of Mingus often recount how his moods would shift in an instant. He would bear his soul one minute, challenge anyone who would listen to a fight, then crack a joke about how strange the ordeal was (all while citing Freud or humming a melody).

But that is the point. There is no real Mingus. There are only passing glances one can use to paint an always-incomplete picture of what Mingus was or could be. But such appeals to uncertainty are not without issues. As the title of this blog post suggests, people wanted the real Mingus. There was a deep desire to find out exactly what made Mingus — here conceived of as a mythic figure more than a living, breathing human — tick. Not all of these desires for understanding were good faith. To Mingus, record labels wanted to define him to exploit him; fans tried to get him so his prestige could rub off on them, and other jazz musicians wanted to be like him so they could steal his glory. To Mingus, defining himself meant trapping himself into a metaphysical prison.

Perhaps this is why Mingus, the ever-enigmatic musician, refused to provide a clear answer to the question. There is no real Mingus because once he is defined, he is a marketable commodity; he becomes an essentialized caricature of his race and himself, and, worst of all, he becomes static and stale. Like his ever-inventive jazz peers, Mingus never wanted to be restricted by the expectations and labels of being a “jazz musician.” Mingus wrote poetry and ballets. His autobiography is a captivating short story about his predicament as a jazz musician. He was a cook and a scholar, but applied too hastily, and the moniker of a “jazz” musician became the box that ultimately restricted him. Mingus’ music is so emblematic of freedom because it, much like the man that wrote it, refuses to be pinned down. If you wanted to discover what Mingus is like when he’s being real, the only way was to keep listening!