Kim Yehbohn Lacey is a Graduate Student Fellow in the Center for the Humanities and a doctoral candidate in the Department of History. Her research interests include the history of empires, transnational migration and the borderlands of Northeast Asia, particularly the Russian Far East, where she studies the overlooked experiences of transnational migrants and the impact of gender, ethnicity and class within the Russian and Soviet imperial projects.

In 1930, a young Russian woman named Nina Vsesvyatskaya moved to the far eastern part of the Soviet Union right after graduating from the Moscow State Pedagogical Institute, searching for adventure. There, she met and fell in love with Cher San Kim, a Korean translator working for a state publishing house in Khabarovsk. They married, moved back to Moscow and had two beautiful children, Alina and Yuliy. The family enjoyed a life full of happiness and bright future.

But on one cold November day in 1937, their world shattered. The secret police, the NKVD, came and arrested Cher San on (fabricated) charges of spying for Japan. The following spring, they returned for Nina. Her crime? She was the wife of an “enemy of the people.”

A punishment for love

Nina was sentenced to eight years in a women’s Gulag, a sprawling network of camps infamously known as ALZhIR. The acronym itself is chilling: the Akmolinsk Camp of Wives of Traitors to the Motherland. When I visited the ALZhIR memorial complex in Akmol, Kazakhstan, during my fieldwork in the summer of 2023, this stark history felt devastatingly present. The thousands of women imprisoned, like Nina, were not political dissidents or criminals themselves. They were teachers, doctors, artists and mothers whose only “crime” was their connection to a man the state had suddenly deemed an enemy. These women were locked up for marrying the “wrong” man.

This form of collective punishment, punishing a person for the actions of a family member, is a terrifying tool that has a long history around the world. It weaponizes our most intimate relationships. The ALZhIR system was the Soviet Union’s version of this on a massive, institutional scale. It was designed not only to isolate the accused but to instill fear in their entire social circle, forcing spouses, children and friends to denounce their loved ones to save themselves. As scholars like Wendy Goldman and Sheila Fitzpatrick have demonstrated, the state-sponsored violence created an environment where ordinary people were mobilized to participate in denunciation campaigns against their close ones. By making family ties a source of danger, the regime sought to ensure that an individual’s primary loyalty was to the state, not to their loved ones.

A collective anxiety

When family ties become a liability, who can you trust? The Stalinist Soviet system thrived on surveillance and reporting, turning neighbors against neighbors and tearing the social fabric apart. The broader horrors of the Gulag were exposed to the world by the Nobel Prize–winning Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. However, the specific, gendered cruelty of camps like ALZhIR remains lesser known. It adds a devastating layer to our understanding of the regime’s oppressive reach into the home.

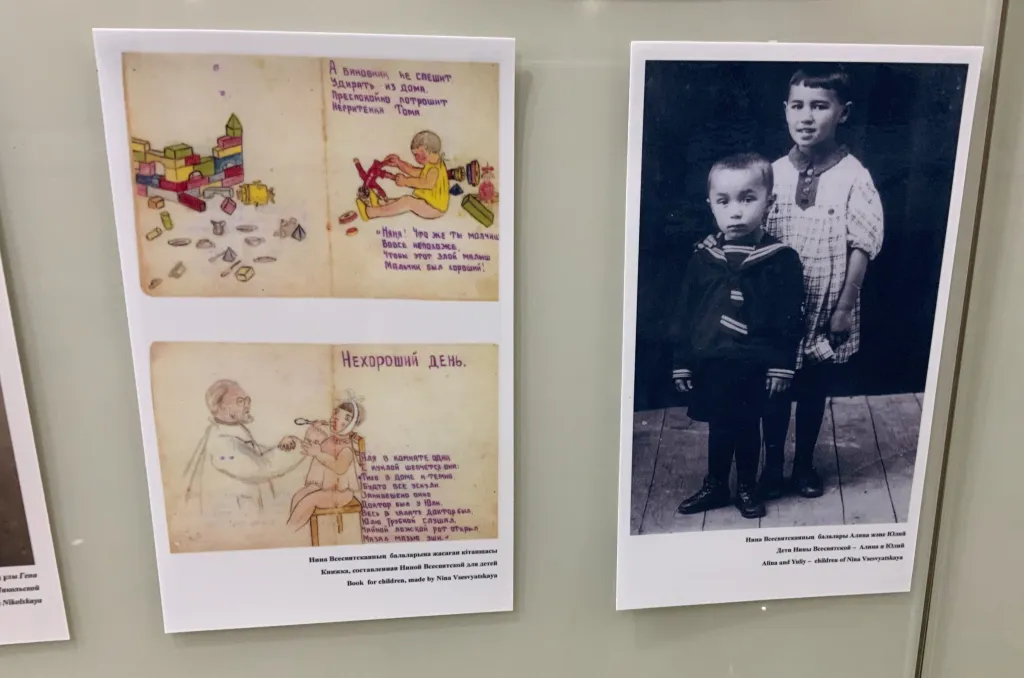

Standing in the quiet of the memorial, I was struck by a display of a picture book Nina had made during her agonizing years in the camp. Separated from her children, who were just one and five years old, and not even knowing if her husband was still alive, she drew. (The family would learn only much later that Cher San had been executed shortly after his arrest.) The simple, hand-drawn pages were a desperate act of a mother trying to remain present in her children’s lives, a testament to a love that the state was trying to erase.

Why it matters now

Nina was finally released and reunited with her children in 1945, long after her husband’s death. Her story, and the stories of the thousands of other women imprisoned in ALZhIR during its existence from 1937 to 1950, is more than just a tragic footnote in Soviet history. It is a profound reminder of how easily the bonds of family and community can be targeted to enforce political conformity.

It shows us that the line between love and crime can be redrawn overnight by a paranoid state. Visiting this place reminds us that to understand the true cost of authoritarianism, we must look not only at the “enemies of the people” but at the wives, mothers and children whose lives were destroyed simply by association.

For more on Kim Yehbohn Lacey’s research, follow this link.

Headline image: Metalwork “Arch of Sorrow” in the background and ALZhIR Memorial in foreground. Photo by Raban Haaijk CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.